In this four-part series, we present municipal policies and projects that offer inspiration and illuminate potential pathways for more sustainable and equitable futures. While each example represents a modest step on its own, together they suggest how municipalities take an active role in building local resilience while taking collective responsibility. These examples arose from our research in two case study cities, Freiburg (Germany) and Grenoble (France), and cover various sectors: waste management, food, housing and advertising in public spaces. They demonstrate innovative—but also contested—ways in which municipalities navigate local development and structural pressures, including fiscal constraints and pressures for economic growth. This blog post marks the start of the series and examines the recent introduction of a packaging tax in Freiburg and its potential implications for municipal finances.

© Rieke Schneider

With the beginning of 2026, Freiburg becomes the third German city to levy a municipal tax on single-use packaging for takeaway food and beverages. This measure aims to address littering in public spaces and resource use – reducing waste generation and easing pressure on municipal waste management. On the surface, the tax can be seen as an instrument to nudge individuals towards the use of reusable options. However, a closer look reveals that beyond individual behavior change, the tax also serves as an example for modifying municipal revenue streams while raising questions around governance and potential pushback. In line with MUTUAL’s focus on the link between policy, practice and urban transformation, we reflect on how Freiburg’s packaging tax may offer opportunities to shift revenue towards resource-based taxation – and possibly away from taxation dependent on economic growth.

Packaging Tax and Reuse System: Sticks and Carrots

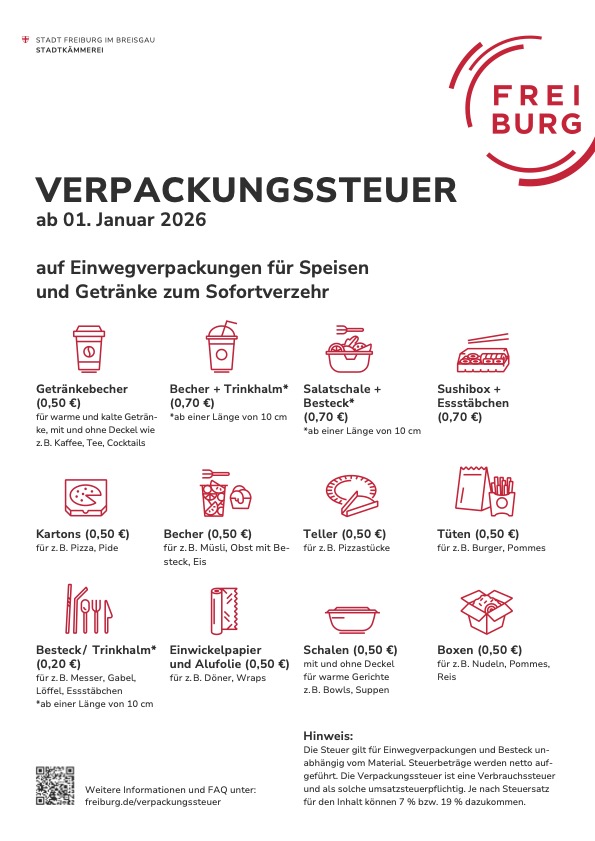

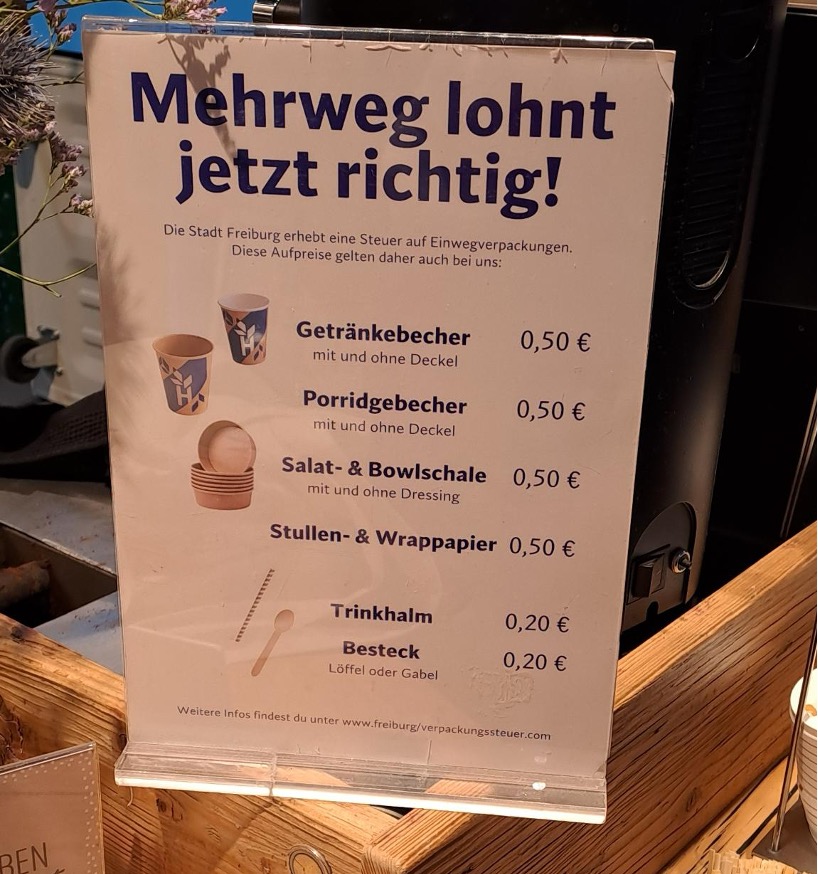

Following a long political dispute at the municipal level, Freiburg city council cast a narrow vote in May 2025 to introduce a municipal tax on single-use packaging for takeaway food and beverages. As of January 2026, the tax applies to disposable beverage cups, takeaway food containers, cutlery and similar single-use items intended for immediate consumption. For each disposable cup, box or other single-use container, a tax of 50 cents will be charged, while single-use cutlery is taxed at 20 cents per item (see photo 2). The tax is formally levied on businesses such as takeaway restaurants, although the costs are likely to be passed on to consumers.

In parallel to introducing the packaging tax, Freiburg has launched a comprehensive reuse initiative (Mehrwegoffensive). Key part thereof is the establishing of a city-wide reusable system (the Mehrwegverbund) that enables businesses to participate in shared logistics, washing, and deposit infrastructure for reusable containers. The city is financially supporting this transition through subsidies for participation costs in the Mehrwegverbund and for the purchase of dishwashers.

Revenue from the packaging tax is expected to reach 2.2 million euros in the first year. After covering annual expenses of around 200,000€ for personnel, the city expects to generate significant net revenue. Of this, 450,000€ has been dedicated to kickstarting the reuse initiative (Mehrwegoffensive) in 2025 and 2026, covering costs for staff, communication campaigns, and subsidies.

Freiburg as Fast Follower

Although Freiburg is among the first German cities to introduce a packaging tax, it drew heavily on experiences from frontrunners Tübingen and Konstanz, which introduced similar taxes in 2022 and 2025. As the first city to do so, Tübingen faced a lengthy legal challenge from McDonald’s. In 2025, Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court upheld the tax’s legality, enabling Freiburg to adopt Tübingen’s now legally robust model.

Early results from both cities are promising. By combining the tax with financial support and information campaigns, both have significantly increased the number of businesses offering reusable options—Tübingen now has Germany’s highest density of reusable-offering outlets. In Konstanz, waste volumes dropped by an estimated 14 tons in the first nine months.

Pushback

The introduction of the packaging tax does not come without challenges. Most notably, Freiburg’s mayor Martin Horn opposed it, citing bad timing amid rising food prices, public frustration with politics and bureaucracy, and limited staff resources (see statement). The tax has also been instrumentalized in a politically charged climate, framed by critics as punishment for consumers, burdensome bureaucracy, and government overreach. These tensions raise an important question: Is the tax’s introduction a bold stand for urban sustainability, or a poorly timed step that risks deepening political polarization?

Packaging tax and municipal revenue

Freiburg’s packaging tax offers an interesting perspective on post-growth principles in municipal governance. On the one hand, the tax explicitly intervenes in consumption practices, making the use of single-use packaging less attractive while offering alternative options. Rather than merely appealing to voluntary behavioral change and individual responsibility, the tax structurally internalizes some of the costs related to single-use packaging such as emissions, resource use, and the costs of waste removal. On the other hand, the tax generates a municipal revenue source based on ecologically and socially undesirable behavior: the use of single-use plastic instead of reusable options. It thus reflects broader post-growth policy proposals for cost internalization and a stronger taxation of resource use.

German cities’ competencies to levy taxes are strongly limited, yet initiatives like the packaging tax can create a potential win-win dynamic: If consumption of single-use packaging decreases, this has positive sustainability effects and waste-management costs fall. If consumption remains high, tax revenues can be used to mitigate environmental and social costs. In this sense, the measure opens up space to diversify municipal income beyond its currently highly problematic base, especially the strongly cyclical business tax.

However, within current system logics, the tax also poses a risk for the city: A reduction in consumption could lead to reduced business turnover and lower business tax revenue – again revealing how closely municipal finances remain tied to economic growth. The experience of frontrunner Tübingen, however, suggests that this scenario is unlikely to materialize.

Ultimately, it is also a matter of framing: The tax contributes to a revaluation of public space and urban commons. By placing a price signal on the use of packaging, and potential litter in public space, the tax implicitly acknowledges the collective value of clean streets, squares and parks. Rather than representing regulation as an attack on market freedoms or a bureaucratic burden, one could interpret the tax also as a form of democratic rule-setting for shared urban life.